QIFVLS held its inaugural NO2DV Community Day in Cairns on Friday 17th October – a highly visible presence in the heart Cairns’ Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community.

Themed, ‘Strong Families Day Out’, the event featured speakers, performers, food vans and fun for the kids. Adults relaxed in the shade of the spreading parkland trees and listened to First Nations entertainers Merindi Schrieber and Simone Stacey, while the young ones wore themselves out on the jumping castle.

NO2DV Ambassador Talicia Minniecon from Mob Made Media was the MC for the afternoon, steering the event with her trademark fun and high energy style.

QIFVLS’ Executive Director Legal, Thelma Schwartz delivered an impassioned address to the crowd, quoting some sobering statistics and stressing the importance of addressing domestic, family and sexual violence within community.

Thanks to Blaq Pearl Indigenous Catering and Mission Australia’s Café One coffee van for keeping everyone sustained.

The day was supported by a range of stakeholder and community service organisations including Kunjar Men’s Collective, Cape York/Gulf RAATSIC Advisory Association, Cairns Regional Domestic Violence Service (CRDVS) and Mookai Rosie Bi-Bayan.

BBM Radio were also there, with an outside broadcast playing live to their listeners.

The NO2DV community event was the first of its kind and sets a template for similar future events across the state.

Townsville Office

Throughout October, Executive Director Legal, Thelma Schwartz and Senior Policy Officer, Kulumba Kiyingi were busy presenting training sessions to community justice groups on the recent changes to Queensland’s domestic violence legislation.

Speaking about the training, Kulumba said, “Coercive control has really forced the forced us to rethink domestic and family violence and the non-physical aspects. As part of the whole tranche of legislation and amendments which have come in, coercive control is front and centre, but there are also additional changes including facilitation and non-fatal strangulation.”

Coercive control legislation

Coercive control is a relatively new term and is a form of domestic violence and is defined as a course of conduct aimed at dominating and controlling another (usually an intimate partner but can include other family or informal ‘carer’ relationships). The controlling and abusive behaviours can create an uneven power dynamic.

Coercive control can sometimes be hard to recognise. Victim-survivors have reported living in an abusive relationship for years without realising that they are experiencing abuse. It can also can involve manipulation and the intimidation of a victim-survivor to make them feel isolated, alone and reliant on the person using violence.

Victim-survivors report coercive control as feeling as if they are “walking on eggshells” and report that they feel a need to ask permission to do small everyday things.

Coercive control legislation snapshot

From 26 May 2025 committing coercive control became a criminal offence in Queensland.

- It is now illegal for an adult to use abusive and controlling behaviours towards their current, or former, intimate partner, family member, or informal (unpaid) carer with the intention to control or coerce them.

- Only people over the age of 18-years-old can be charged with the coercive control offence: section 334C(1)

- The criminal law offence is found in Chapter 29A of the Criminal Code Act 1899 sections 334A- F.

- It is immaterial whether the course of conduct actually caused harm: section 334D(2)(a)

- The maximum penalty is 14 years imprisonment: section 334C(1).

Facilitation legislation

The standard conditions for a police protection notice and a domestic violence order now includes a condition that the respondent must not encourage or engage another person to do something that, if done by the respondent, would be domestic violence against the aggrieved.

It is now an offence if the perpetrator asks, encourages or forces a family member or extended kin to do something that could be considered associated domestic violence. This includes:

- Monitoring or tracking the victim-survivor;

- Harassing the victim-survivor to drop the DVO or police charge;

- Trying to find out where the victim-survivor has moved to.

Other changes to DV legislation

During the sessions , Thelma and Kulumba advised participants that the Queensland Law Reform Commission (QLRC) was reviewing the offence of ‘Non-Fatal-Strangulation’ in the Criminal Code – particularly clarifying words, ‘choke’, ‘suffocate’ and ‘strangle’. The QLRC provided a final report to the Qld A-G on 30 September 2025 and legislative amendments are expected in the coming months.

Fresh out of their DV legislation training with community justice groups, this month’s Blakchat features Executive Director Legal, Thelma Schwartz and Senior Policy Officer, Kulumba Kiyingi talking all things policy reform.

Check out the half hour chat by clicking on the picture.

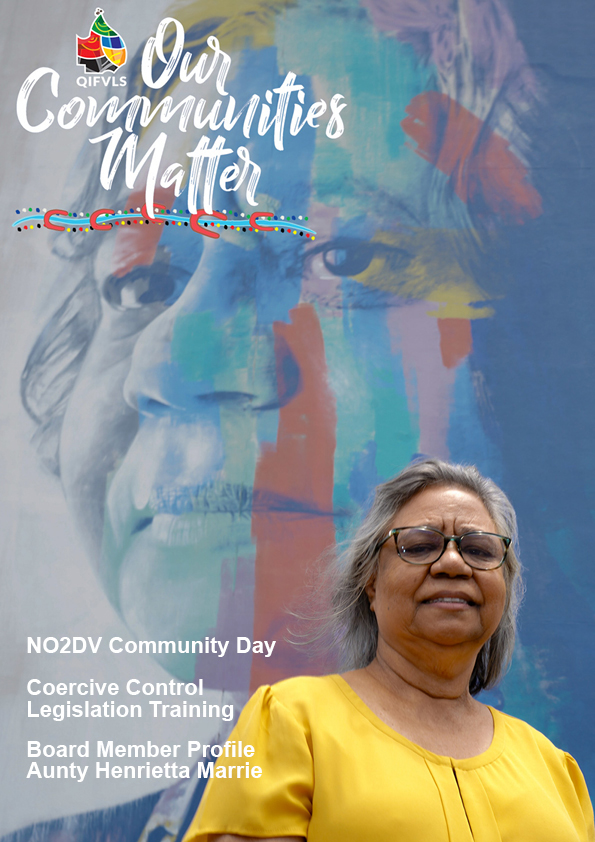

OCM: Thanks for sharing your story with us Aunty Henrietta. Tell us about your upbringing.

Aunty Henrietta: I was born and raised at Yarrabah, an Aboriginal community south east of Cairns. My tribal groups are the Gimuy Walubara Yidinji people through my father, and my mother’s tribal group is the Gungandji people.

We have unbroken connection to this land of Gimuy/Cairns, Yidinji country. My grandfather was Ted Fourmile and my great grandfather, Ye-i-nie, was a great warrior and leader of our tribe. There’s many photographs of him that you can find here in Cairns, including on the Esplanade.

I grew up in Yarrabah where I did all my primary school years before going to Palm Island where my father got a job as a Liaison Officer with the Department of Aboriginal Affairs during the early 1960s – just one of 10 who were trained.

OCM: What do you recall of your time growing up in Yarrabah?

Aunty Henrietta: Yarrabah was a place where I was able to really be in touch with the land, culture and the country – and particularly with our cultural stories and heritage. Two of my grandmothers were sent to Yarrabah at the age of seven and eight years old. They’d been taken away from their traditional territory in Cooktown and Wujal Wujal. I got to know some of their stories, and also those from my great grandmother, Granny Jinnie Katchewan who was one of the Elders and leaders there. I always recognised her as a lore woman from when it was first established in 1892. I was around two years old when she passed. I learnt a lot about culture and traditions like gathering seafood, eating mango and collecting bush tucker. Family and Kinship was very important in those days and still are today.

I think the beauty of Yarrabah back then was its isolation. The only way in and out at that time was by boat. The road wasn’t built until the late 1960s or early 70s.

During that time Yarrabah fairly self-sustainable community. We had farms where we grew vegetables and fruit, and our own abattoir where fresh meat was always available. And of course, on top of that, we had access to the traditional food from the sea, rainforest and the coastal areas. We also had a sawmill where timber from Badabadu was brought in to be cut. The timber was used to build houses in Yarrabah and also taken to other communities throughout North Queensland. The sawmill at one time was managed by my grandfather and then later on by my father. The fact that we were sustainable meant we were not dependent on the Government or outside industries.

I was about nine when my father was selected to be trained as a Liaison Officer. After six months of training in Brisbane he was sent to the mission on Palm Island, where we followed later. I spent the next three years attending boarding school in Townsville .

Palm Island back then was a segregated community similar to apartheid like South Africa. It had a separate school for the white students, and the picture theatre was also separated so the whites would sit at the top and the black community would sit downstairs. The store was exactly the same, and the post office, so I got an early understanding of policies that treated First Nations people differently.

That was a great insight for me, even though I didn’t quite understand it then. But what I did understand was that my father would not accept it. Together with some of the Elders of the Palm Island community, they decided to make a strong statement and strike down any kind of structure which treated people differently.

The cafeteria in the picture theatre had two windows – one window to serve the black families and another one to serve the white families. So dad nailed down the window that was serving only the white community, ensuring everybody had the right to use the one window, to be served at the cafeteria and to sit wherever they liked. He also sent the rest of my siblings to the public school so everyone would learn together.

After that we moved to Mareeba on the Atherton Tablelands near Cairns, where I finished my final years of schooling. I found that living in Mareeba was a very different society indeed, coming from a mission to living in a township full of non-Indigenous people, you really had to learn to survive.

There were lots of farms in the area, where we’d work over the weekend. It was a family thing – top and tailing onions and bagging them, and stringing tobacco leaves. It taught me many things, like being independent and working to earn your own money. Learning about work ethic gave me a good start in life.

OCM: Did you have a bit of a plan for your life at that stage?

Aunty Henrietta: No, I didn’t. I had no idea what I was going to do. After high school I went to business college in Cairns. I would travel by train on the train from Mareeba to attend college on Mulgrave Road, Cairns. After I finished, a number of us girls were invited to go to Canberra to work in the typing pool for the Commonwealth Government.

OCM: The early 1970’s would have been an interesting time to be in Canberra, which was becoming more socially progressive.

Aunty Henrietta: We were there when the tent embassy went up and there were demonstrations going on with Aboriginal people coming in to march – it was a great time! We saw a lot of Indigenous people there who became influential community leaders, like Kath Walker, Oodgeroo Noonuccal and Chicka Dickson from New South Wales. Chika was a very strong leader and had a big influence on my life.

OCM: That period may well have helped to form your political or policy perspective.

Aunty Henrietta: I became very much aware of the political movements during my days on the mission and watching my father and mother over the years. You don’t have to be removed from society to create change. For me, it was normal to sit down across the table from a white person or working with Government departments to make decisions or debate issues.

OCM: How long were you in Canberra for?

Aunty Henrietta: I left after a couple of years to come back home and got married, and had my first daughter. I also worked as a Liaison Officer at a school in Mareeba and for the Tablelands region.

Then I went to Adelaide, to the University of South Australia where I completed three degrees: A Diploma in Teaching, Graduate of Arts and Indigenous Politics and Indigenous Studies. I later went on to complete a Masters in Environmental Local Government Law.

I always say that I found myself when I went to Adelaide – it gave me the opportunity to reflect on the lifestyle I grew up with in Yarrabah and realised that it was very similar to the traditional lifestyle of the Pitjantjara people in the northern part of South Australia.

It was while living in Adelaide that I learnt about the cultural artifacts, photos and other important objects from Cairns and Yarrabah, which had been taken from my country, Yidinji country and Gundghi country, and locked away for many years in the South Australian Museum.

So I went on a quest to find out more about them and to seek authority to bring them home. I found a lot of the shields and the designs and the boomerangs and spears were linked to families I still knew, even though they dated back 100 years.

Incredibly, while the museum had over 100,000 Indigenous items from everywhere in its collection, there was only one Aboriginal person working there at the time. I started questioning this and formed a group to challenge the museums, their policies and laws.

It motivated me to write about this experience which became one of my first papers on institutional racism, using the South Australian Museum as a case study.

Adelaide was also where I met my husband, Adrian. He was instrumental in getting me into the museum to look at the Indigenous collections.

I had been invited to do my Master’s Degree in Environmental and Local Government Law at Macquarie Uni, which I took up, but first I needed to get these Cairns and Yarrabah artifacts home. Repatriation was impossible if you didn’t have your own keeping place. My cousin was working at Yarrabah council and, with the support of other council members, they lobbied to build a museum in the community to create a dedicated home for the items, which was ultimately successful.

In 1987 we went to Brisbane, after I successfully gained a position at the Mt Gravatt Campus of the CAE, now known as Griffith Uni. I became one of the first lecturers in advanced curriculum development, and the first Indigenous woman to lecture in that space.

Our next stop was home, back in Cairns in 1991. We needed to get back – my parents were getting on in years, and I just wanted to be around them again and for them to be able to connect with their grandchildren.

I worked at the TAFE for a little while, and then at James Cook Uni, heading up their Indigenous campus. I remember that as a great period – working alongside the 100 Indigenous rangers-in-training.

In 1996 I applied for a job with the United Nations Environment Program – Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity in Montreal which had been advertised. I applied and was successful! We left Australia the following year, which was a huge move. A different country, a different culture and a different language. I only had high school French, so I had to take a refresher course in the language when I arrived in Montreal.

We had lunchtime language courses as part of the United Nations staff development where we could take classes on any UN language we wish to develop our knowledge to advance our position . I was doing a lot of work with the Spanish government at the time so I learnt Spanish as well. Unfortunately I’m not very good at these languages anymore.

I had been at the UN for six years and after giving a presentation at New York University, someone from the audience approached me. He introduced himself, said he was going to manage a new philanthropic organisation in Palo Alto, California and asked if would I be interested in working there?

After giving it a lot of thought I agreed and we moved to the States in 2003 to join the US based philanthropy ‘Christensen fund’. During that nine year period, I brought about $35 million into Australia for Indigenous management of land and resources, cultural biological diversity and advancement.

I worked with many philanthropic organisations in Palo Alto and California. What makes me proud is that many of the community organisations that were beneficiaries here in Australia are still operating today, over twenty years later.

My UN job had me travelling all over the world. Although I was based in California, the role took me to Canada, Europe, Spain, Japan, South America, Africa, the Pacific and so many other different countries.

My time there offered some really great insights into the United Nations, and how we could make changes within the UN Convention on Biological Diversity. The UN Convention had reference to Indigenous and local communities on a global scale, which amounts to about 1.2 billion people that they were servicing in the Middle East, Africa, the Pacific, the Caribbean, South America and North America, and in Australia of course.

OCM: What would a 16 year old Henrietta have thought about the life you ended up living?

Aunty Henrietta: I don’t know, I was having a great time enjoying my life living with my family in Australia and not even thinking about where I was going to end up. I never knew I’d even leave Cairns, Canberra or Adelaide. When I had my first meeting in Fiji, that was probably as far overseas that I thought I’d ever go.

OCM: When did you become involved with QIFVLS?

Aunty Henrietta: When I came back from overseas I got to know Barry Doyle, who was QIFVLS’ Chair at the time, and Rose Malone who is still there, and was invited to join them on the Board.

OCM: How have you seen the organisation evolve?

Aunty Henrietta: Gosh, I’ve seen QIFVLS grow. I’ve seen the CEO Wynetta Dewis strengthen in her leadership and take QIFVLS to another level. I’m proud to be part of it because we’ve really moved further ahead in supporting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

I’ve watched the development of the organisation’s leadership, through great staff that work there, and through the other Board Members who have a vision and passion to take QIFVLS to great heights.

OCM: Finally, what does Henrietta do when on her time off?

Aunty Henrietta: Probably nothing other than cultural activities. I’m always trying to do things for Gimuy. We’ve worked on addressing institution racism in the health system and hospitals and we’ve just completed a bigger project to do with the justice issue. I think these are the matters that will probably dominate my life for a while. And more importantly, taking on my role as Grandma.

OCM: Thank you Aunty Henrietta.

When an individual or organisation makes a tax deductible donation to QIFVLS, they can be confident that their funds are going towards making a tangible difference to the safety and welfare of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people experiencing or at risk of domestic and family violence.

Our team are grateful for all donations that help our not-for-profit organisation to continue offering this critical service. Donations of $1,000 or more help fund outreach services to some of Queensland’s most remote ATSI communities.

Are you in search of a rewarding profession that will take you on journeys through the breathtaking landscapes of Queensland? One that promises not only career advancement and skill enhancement, but also attractive perks, substantial travel allowances, and one-of-a-kind professional adventures? Are you drawn to a career that enables you to make a positive difference in the lives of others?

Look no further – your new career awaits you! At QIFVLS, we are dedicated to combating Family and Domestic Violence within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities. Our methods encompass education, advocacy, legal reform, court support, and casework assistance. By focusing on early intervention and prevention, our aim is to empower individuals impacted by Family Violence to regain control over their lives. We are in search of outstanding and dynamic individuals who can join us in achieving this mission.

If you envision yourself fitting into this scenario, we encourage you to see what’s available here.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.